Bryan R. Monte

AQ44 Autumn 2025 Book Reviews

Jennifer Clark. Intercede: Saints for Concerning Occasions. Unsolicited Press, 2025, ISBN 978-1963115390, 170 pages.

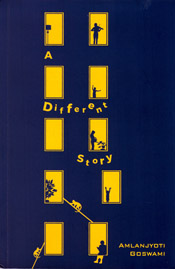

Amlanjyoti Goswami. A Different Story. Poetrywalla, 2025, ISBN 978-81-984437-9-3, 241 pages.

I received five requests for book reviews over the summer. Not all of these titles caught my interest, but two really stood out because they were especially well-written, and coincidentally, both encyclopaedic in scope. Both are by past contributors to Amsterdam Quarterly. The first book is Jennifer Clark’s (AQ14, AQ17, AQ20, and AQ23) Intercede: Saints for Concerning Occasions about various Christian saints, from the first through the 20th centuries. The second is Amlanjyoti Goswami’s (AQ28, AQ29, AQ33, and AQ40), A Different Story, which offers various takes on a myriad of subjects such Indian customs, religion, letters, history, music, and travel, along with the poet’s love for his hometown, family, film, and particularly poetry.

Intercede: Saints for Concerning Occasions confirms that Clark is not only a poet, but also a scholar. It follows in the footsteps of her previous and similarly well-written and historically researched poetry book, Johnny Appleseed: The Slice and Times of John Chapman. In Intercede, Clark covers a panoply of saints from the first century to the 20th. She investigates their spiritual qualities and their method of selection (originally vox populi before papal canonization was formalized in the 12th century). Intercede’s poems describe the well-known, such as Sts. Ambrose, Andrew, Catherine, Denis, Jerome, Joseph, Lawrence, Martin de Porres, Monica, and Nicholas, and the more obscure such as Sts. Appolonia, Drogo, Jeanne de la Noue, Juthwara of Cornwall, Thecla, Vitus, and Wilgefortis. Clark’s catalogue even includes a Job Posting for Sainthood with the required skills and experience perhaps for application. It is Clark’s thesis, borrowed from St. Mother Teresa of Calcutta, that it is not the miraculous that makes saints extraordinary, but rather their ordinary lives which they lived extraordinarily.

However, Intercede isn’t a dry, ecclesiastical tome. Clark’s erudite but accessible poetry and humour brings these saints, even the mythological ones such as St. Ursula, or the creatures they fought such as St. Columba’s battle with Nessie, that never lived, back to life.

Another reader-friendly feature of Clark’s saintly collection is that 60% is traditionally versed, while the other 40% are prose poems. I imagine this is for those Catholic school students who were scarred not only psychologically but also physically by ruler-wielding, knuckle-whacking nuns, who not only enforced the punitive memorization of poetic lines, but also their scansion.

Clark’s connection with Amsterdam Quarterly also goes way back. Long before she completed Intercede, Clark sent AQ her poem, ‘Saint of the Broom, help us learn your sweeping ways’ for consideration for publication in AQ20 in July 2018. This poem describes St. Martin de Porres: a poor, illegitimate, mixed-race, young man, who overcame prejudice through the simple act of sweeping. ‘(F)or eight long years, you swept your way through the friary’… ‘and made a clearing in the heart of the Dominicans’. Martin continued on his upward path, next as a brother…(who) ‘tended the garden, planted orchards of olives and oranges, lemons and figs.’ However, when asked by his fellow friars to poison mice, who were ‘chewing the altar linens’, Martin instead ‘whispered in the(ir) ears’ (leading them)…to ‘a safe path to the garden.’ Clark writes it wasn’t his ‘abilities to levitate, bilocate, and heal,’ that made him stand out, but rather his ‘leaning in corners, unobtrusive, humble as a broom.’

Clark’s uncommon and/or humorous approach to saintly lives is most apparent in her poem about St. Lawrence, ‘Patron Saint of Cooks and Comedians’, which begins in the form of a traditional bar joke and also gives a bit of early Christian history including the martyrdom of St. Sixtus II.

A saint walks into a bar packing a punchline

It’s 258 A.D. and Saint Lawrence’s friends’ heads

are rolling in the aisles—including Pope St. Sixtus II.

Clark conveys this persecution through more comedy metaphors: ‘Rome, the opener, is just warming up.’ It demands Lawrence ‘hand over the riches’ (to the church) / or else he’ll suffer a similar fate.’ The poem further describes ‘the poor/ as his main audience’ to whom he gives the churches riches instead of the state. It concludes with:

Rome roasts him on a gridiron. Rome thought it killed

but it is really Lawrence, on fire with Christ, who kills

that night. His closing line is perfect. “This side’s done,”

he quips. “Turn me over and take a bite.”

In 2011, I visited the Church of St. Lawrence in Perugia with students from a memoir writers’ workshop in Assisi, led by Philip Lopate. These students might not have known much about Christian martyrs, but they could all recount the ‘turn me over’ quip about Lawrence as well as ‘The first step was the hardest’ remark about St. Denis, who walked six miles into Paris after being beheaded.

However, Clark does not present being a saint as all fun and games. St. Columba admonished the Loch Ness monster to ‘go back with all speed’ and ‘She fleed…and never killed again.’ Other saints such as Sts. Gemma Galgani and Hedwig practised self-mortification by wearing hairshirts, chains, and flesh-piercing spikes. The former, in an act of extreme penance, threw herself into a well. (It’s said that an invisible hand pulled her out. She died of tuberculosis.) St. Simeon found monastery life too luxurious, so he lived, preached, and shat atop a plinth in the open for 36 years.

Clark’s list of Christian saints also includes some DEI picks: a forgotten early female evangelist, who preached, baptised, and conducted services in the first century, a possible intersex saint to whom women prayed to be freed from their husbands, and three Black popes who later became saints. The female evangelist was Saint Thecla, a contemporary of the Apostle Paul. In the second century, her sayings were collected in the Acts of Paul and Thecla. However, over the centuries she and her message were forgotten due to later institutional misogyny. Clark’s St. Thecla says:

…I fade away in a cave near the Aegean Sea where someone in the

sixth century painted me standing next to—and equal to—Paul, though

someone has come along and blinded my eyes and scratched the raised

fingers of my right hand. As if that could take away a woman’s power.

Clark also mentions St. Wilgefortis, also known as Saint Uncumber, to whom women prayed to be freed of their husbands. She was a Christian woman who ‘begged God / to make her ugly, the only / way she could think to sheer / the suitor from her side.’ Although she was able to grow a beard because of her prayers, nonetheless, ‘her pagan, Portuguese King / of a father would crucify her.’ Clark’s poem, ‘Three Black Popes’, tells the story of three men of colour who led the church during its first six centuries, who were later canonized. The first was Victor in the 189, the second Miltiades in 311, and the third, Gelasius in 492. (Unfortunately, Pope Gelasius ‘condemned the Acts of Paul and Thecla as apocryphal.’)

Clark’s saints also include those closer to home: her family and some of their friends, who were wise and kind. She even includes one concrete poem in the shape of half a ship’s hull, ‘Underwater Jesus’ in memory of Gerald Schipinski and sailors killed in boats on the Great Lakes. According to Clark’s notes, Shipinski lived Bad Axe, Michigan and was accidentally killed in 1956 by a shotgun he’d just received as a fifteenth-birthday present, while driving a tractor. His parents purchased an 11-foot crucifix to memorialize him, but it arrived broken. This cross was purchased by the ‘Wyandotte Superior Diving Club’ and later ‘repaired and maintained by another Michigan diving club’ … ‘Today it serves as a memorial for divers who lost their lives in the Great Lakes.’

However, what I found as the most outstanding saintly characteristic in Clark’s roll call of saints, was their ability to forgive grievous harm done to them by another or to sacrifice their lives for another. Two saints that fit this bill are Sts. Maria Goretti and Maximillian Kolbe. St. Maria Goretti was twelve when she was murdered by a 20-year-old man, who stabbed her with an awl 11 times in the chest and three times in the back. As she lay dying, she forgave him. She later appeared to her brothers in dreams advising one to go to America to seek his fortune, and he did. St. Maximillian Kolbe was a priest, who gave up his life in a Nazi concentration camp for another, who was selected for execution.

Clark’s poems and notes are reinforced by frescos, block prints, illustrations, engravings, etchings, icons, paintings, and photos ranging from the medieval to the twenty-first centuries. All help illuminate the persons in Clark’s pious catalogue: Intercede: Saints for Concerning Occasions.

Art also plays a role in Amlanjyoti Goswami’s new poetry book, A Different Story. Its front and back covers feature a five-story building with two windows per floor. In some of these windows are silhouettes of children, large plants, a woman watering a plant, a violinist, and a bald man sitting on a window ledge on the front cover and painting a wall on the back, (perhaps the poet himself), along with monkeys climbing up electrical or communications wires. This cover provides a visual context and an additional meaning for the book’s title. It is a very large collection of 235 poems divided into nine sections: Wonder, Sorrow, Courage, Laughter, Anger, Fear, Compassion, Love, and Peace. This is the poet’s tribute to the nine rasas of Indian aesthetics, which serve as emotional foundations of being. The book is dedicated to ‘all the lonely people who long for a different story.’ The poets’ subjects include art, books, music, history, both personal and general, death, Indian geography, weather, culture, religions, and rituals, as well as references to ancient and modern writers and artists such as Horace and Fellini.

Section I: Wonder, with the epigraph, ‘Sometimes the sky sees me’, starts this book off with a bang with a poem, ‘Turning Points’, about the events that are traditionally considered historic such as battles, thrones, and rulers. Instead of these standards, the speaker mentions three aspects of what he considers history: ‘…if the way you came back is different from the way you left.’ / …if no one remembers you anymore, even those you once knew.’ / …(if) during oral renderings of life stories…/ you moved someone from stone.’ So, right at the beginning of his book, the poet has set himself a tall order.

Section II: Sorrow contains many of the book’s elegies: to the poet’s mother, the Indian jurist Fali Nariman, Indian classical musician Ustad Rashid Khan, and US poet and 2012 National Book Award winner, David Ferry, among others. In fact, this section begins and ends with poems about Goswami’s mother, a central figure and recurring figure in A Different Story. In ‘It’s only 4 a.m.’, the poet is present as his mother passes:

Ma left in my arms,

quietly without attention.

The machine beeped a little

And then she was gone

The poem includes memories of what his mother liked: ‘sea breezes, folk songs / Passages from the Gita / And lines from classic poems.’ Towards the poem’s end, Goswami sums up:

In life, she was life.

In death, she is an absence.

Goswami memorializes these people’s so simply and clearly that I felt in some way that I had known them too. In addition, these poems, especially the one above, could also be used as models for elegies in creative writing classes. The poem that bookends this section is entitled: ‘Ma did not see Bombay’ Its lines include:

Ma is gone from this world

And I don’t want to call her back

Now that she is wind, and sometimes rain

Section III: Courage begins with ‘Graduation Ceremony’, a poem which compares how ‘Grandmom continues to find meaning in small nuggets.’ while ‘her granddaughter wants to change the world.’ In ‘Baroda Pharmacy’, a child comes in with ‘a gash on the right arm, blood oozing’ instead of going to ‘the hospital next door.’ Nonetheless, the pharmacist cleans and dresses the wound. Section IV: Laughter captures the more sophisticated world of a slightly older narrator. It has many poems about inspiration, including the value of coffee ‘A good filter coffee is hard to find’, going to a traditional healer in the market for a dislocated limb, ‘Bonesetter’, film and the imagination, ‘Fellini asked me for a smoke’, procrastination, ‘Reasons for Delay’ , and the hope for success as a writer in ‘Success’.

In the first poem of Section IV, ‘From a small town which loves sleeping’, the poet tries to define

The urge to write

What this means to me.

Light streaks an open door

Ideas and mosquitos come in.

Later in the poem, the speaker mentions the strange feeling of (self)-exploration poetry gives and the paradoxes it can create:

Time standing empty

When I step into my own shadow

To greet the stranger

I’ve never met before.

In ‘The Perfect Line’, Goswami writes about his difficult and sometimes interrupted pursuit of inspiration that ‘came to me while sleeping’ or ‘was hiding somewhere.’ or ‘Never arrived’.

However, Goswami’s poems aren’t only about the personal and the artistic. ‘Final Settlement’ is a political poem and a detailed, categorical summary of the Union Carbide tragedy that killed and injured thousands in Bhopal, India in December 1984. In another poem, ‘War Clouds’, the descriptions could be applied to armed conflicts and political oppression in many places around the world: ‘Those who come in armour / Knock at a midnight door / Raining bombs on those with no umbrellas / Who think it is mere spectacle’

Yet, Goswami does return to his family and his mother over and over again. In ‘My Mother wonders about Poetry’:

My mother asks where these lines lead her

She asks: why poetry?

A few verses later,

She wonders if words have taken over my life

Just like some people are possessed.

By a will to live

Others by a wish to die.

Likewise in the poem ‘Light & Shadow / What the Greeks knew’ the poet emphasises the contrast between the temporality of the human body versus the mind’s awareness of the cosmos’s eternity.

Goswami also has several typographic experiments in this book. His lines in the second half of the later verses of ‘When my mother ran down the Street’ veer progressively farther away from the left-hand margin replicating the earth’s movement in a 6.5 earthquake, as told by a young man. Another poem, ‘Man in the Crowd’, the lines are right adjusted as in Urdu or Persian writing. It describes an older, legendary poet, Ghalib, who queues with the other people on the street waiting for food to be distributed. Once he has eaten, he smiles and ‘become(s) the Ghalib of old / and shares some secrets only he knows / Where poetry lives these days and what she likes & why / She doesn’t enter our hearts as often.’ Another centred poem is ‘What the poet Needs’, whose first verse is immediately engaging: A poet doesn’t need much. / Just the universe / And its broken shadow. A third poem with scatter shot, short lines, some with only one or two words, similar to William Carlos Williams’ variable foot is ‘The day she forgave her father’s killer’. Sometimes the two speakers’ lines are on opposite sides of the page, but sometimes when they try to reach some closure and/or a middle-ground, they are in the middle of the page.

Section VII: Compassion has many poems about readings, wisdom, poetry and poets themselves, and also about translation. This section begins with ‘A Gathering’ where ‘Old colleagues gather in the common room / To read out poetry to each other.’ // A guitar strums in the background. / Today is not for theory.’ / but for music arriving slowly.’ Towards the end of the poem, the speaker relates: ‘When the room is filled with light / Verse enchants listeners with second sight. There are also more than a few unconventionally spaced or aligned poems in this section also. These include ‘A Visitor’, all of whose lines are in centred mode, about an old, very well-dressed man, who comes to sit on the veranda and watch younger people play in the sunset. The speaker admits ‘We didn’t know what moved him. / But we were gracious and let him be.’

It’s a bit of journey, but finally in Section VIII of IX, on page 206, is the book’s title poem, ‘A Different Story’, about the different kinds of stories, how they unfold and how they exist without a reason:

Some stories exist because they do.

The best have no morals.

They quietly fold into a bed sheet

& step out before morning.

Others stare long nights, howling with pain.

Some enjoy a good night’s sleep.

However, The speaker also includes love poems on his list, which he says:

They believe in themselves, breakfasts & long evenings

These too exist without a reason.

The last section, IX: Peace, is composed largely of meditative and a few ekphrastic-like poems, which are dedicated to centring perception and the heart. It begins with the observant poet ‘sitting on a monastery bench watching leaves fall’ in which he sees ‘on my left, gray clouds advance stealthy as a platoon…on my right, closed doors of perception / remain locked for today.’ Two poems later, ‘The Heart of Silence’ appears to be in the form of a person sitting in meditation, centred in the middle of the page, trying to achieve its title’s state. ‘I am describing the heart of silence / The way I have been taught / Which is to say, with the least words possible’. In this section, the speaker tries to describe his illumination, sometimes with the help of art such as that by Pissarro and Hopper. For this reviewer, it has been a long journey, but well worth it. It has changed both the narrator and the reader. AQ