The Long Workshop: A memoir of Thom Gunn, 1982-1994

by Bryan R. Monte

I first met Thom Gunn in January 1982 at the University of California, Berkeley as a student in his creative writing workshop. Strangely, even though we lived close to each other in Haight-Ashbury the previous year, he at Cole and Alma and I at Haight and Clayton, nine blocks away, we had never run into each other at neighbourhood or gay-themed readings or parties. (Haight-Ashbury poet and friend Steve Abbott, however, promised he would introduce us if we ever did).

I didn’t know what to expect from Thom personally, though something about his poetry “spoke to me” years before I knew he was gay and I had moved to San Francisco. My first contact with his poetry was during my last year of high school as I prepared for the Advanced Placement exam in English by reading through the Norton Anthology of English Literature from cover to cover. His poem “Human Condition,” about walking through a fog “Contained within my coat”. The phrase “…condemned to be/An individual,” certainly resonated with my teenage angst, growing up gay in Ohio. It was also consistent with all the walking around I did looking for who knows what, trying to quiet the ever-turning wheels in my head.

Two and a half years later after I had returned early from a mission to Germany due to a nervous breakdown, I received The Poetry Anthology 1912-1977 from my senior high school English teacher as a New Year’s gift to help me recuperate. The book featured Thom’s young face at the top of the book’s thick spine with a young Tennessee Williams in the middle and a matronly, 19th century looking Harriet Moore, the magazine’s editor for many decades, smiling at the bottom. This book contained three of Thom’s poems—“High Fidelity,” from 1955, “The Unsettled Motorcylist’s Vision of His Death” from 1957 and “The Messenger” from 1970. All of these poems are formally constructed, but the rebellious, young man seemed nonetheless to burst through these restrictions.

This is one of the few books from that time, before college, that I’ve kept all these years and certainly one of the few I had with me when I moved to Haight-Ashbury in 1980 to find out what it meant to be gay in a more tolerant environment and to see if I could be a writer. I think I considered it phenomenal for a living poet to have one poem in the Poetry anthology, let alone three.

At Steve Abbott’s urging I purchased two copies of Thom’s books from a second-hand bookstore. These were the thin, 47-page, chapbook length, My Sad Captains (1961) and the somewhat thicker, 78-page, Jack Straw’s Castle (1971). So these two books, published almost a decade apart, had launched and maintained the great man’s career, I thought.

From the very first day class, I knew Thom was going to be different than the other male Berkeley professors. Instead of coming to class in a button-down shirt and tie, chinos or jeans and a wool jacket with elbow patches, Thom arrived wearing a tight, white, round-neck T-shirt, tight Levi’s black jeans, black biker boots including the silver chain back by the heel, and of course, a leather jacket, the scent of which filled the room as his body warmed it. In contrast to his tough guy, rebel-without-a-cause wardrobe, however, Thom proved from the very beginning to be a somewhat shy, soft voiced man, who, nonetheless, commanded the respect of all his students without (as far as I can remember) ever having to raise his voice to call the class to order.

To fill the time during the first meeting, Thom had us introduce ourselves around the circle. (Yes, as a former educator, I’m shocked to realize that this was the one and only class at Berkeley that I can remember in which the classroom chairs were arranged so radically!) The students generally introduced themselves and talked briefly about their writing interests and experience. I don’t know what I said about myself that day, but I remember one or two students mentioning university poetry awards they had won or that they were putting a (chap)book together.

As far as my background was concerned, I’d written about two-dozen, short, imagistic (and some homoerotic poems), which I’d submitted with my admission’s essay to Berkeley. This had earned me a blue, “Do Not Admit Under Any Circumstances” sticker on my admission folder, but that’s another story. These same poems this time, however, were good enough to get me into Thom’s class. In fact, for the next 20 years, Thom’s workshop was one of the few I attended where sexuality of all kinds could be freely used and discussed in poetry.

Five fellow classmates mentioned in my journals include L.R., a short, dark-haired lesbian, Taras Otus, a blond, laid-back Southern Californian with a calm smile on his face that reminded me of Yoda from Star Wars, Miles, a shy, sixth-year undergraduate who wore a broad-brimmed, light-tanned, Australian hat with corks hanging around the brim during class, Cindy Larsen, a Mormon wife and mother, and another woman whose name I think was Marina, who wrote a poem about a homeless man or woman who everyone passed on their way to work. The terminal lines to her poem, as I remember them, went something like this: “How do you sleep at night/ knowing he/she’s on the street/ and you, in your safe, soft, clean bed./Very well, I bet.” It exemplified the smugness and lack of social consciousness of the Zeitgeist as yuppies gentrified San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury, Western Addition and Castro neighbourhoods (some “homesteading” as they called it with guns next to their beds and bars on their windows). It also typified the new breed of Berkeley students who seemed more interested in buying clothes than books as more stores devoted to the former opened on Telegraph Avenue replacing the latter.

After the dozen students had introduced themselves and their poetic backgrounds and/or aspirations, Thom explained the rules of the workshop. Students were to submit work twice during the quarter. These submissions could be four short poems (shorter than one page), one long (longer than two pages) and two short poems or two long poems. The poems were to be photocopied and distributed a week in advance of class so that students could make micro and macro annotations about the manuscripts under discussions. Each student was allowed five minutes time to critique the poem before the discussion moved on to the next speaker. Students who had not read and annotated the poems in advance of class were not welcome to critique the poems.

In addition, while a poem was being critiqued, its author was to remain silent and take notes. Only after the critique was finished (usually after a half hour maximum) was he/she allowed to speak and then only to address questions posed by the readers to fill in missing details such as: “Who is speaking here?” or “What colour was the stone?,” etc.

Thom then gave us a stack of handouts about the basics and nomenclature of rhyme and rhythm and also a short collection of representative modernist poems including an excerpt from Basil Bunting’s Briggflatts (which, to his horror, Thom discovered none of us had heard of).

I soon discovered that Thom was a humble, professional, impartial, caring and reserved instructor. He never took up class time telling old war stories about his time with other famous poets and writers. For example, he didn’t mention his Stegner Fellowship to Stanford to study with Ivor Winters or his journey down to Santa Monica to visit Christopher Isherwood. He also didn’t “testdrive” new poems in class. Furthermore, even though Thom was gay and he knew I and some other writing students were gay, as far as I know, he was one of the few gay instructors who respected the barrier between instructor and student. Moreover, he didn’t groom protégés for class or for the poetry contests he judged.

In Thom’s workshop the students’ writing was the most important thing week after week. I don’t ever remember him giving us specific assignments like those I’ve had in other classes which half of the time, the teachers haven’t bothered to check or review in class such as: “Go write a poem from the perspective of an animal of a tree,” or “Imagine you’re attending your own funeral, what would you want someone to say about you in verse?”

Thom was very secure in his role in the class. He just left us to the business of writing and he used the students’ texts as the examples from which he taught. In addition, I don’t remember Thom ever talking about grading as most professors did during their first classes, nor mention participation as a means of boosting one’s grade.

One last very important aspect about Thom’s workshop that stands out took place in the second class when student work was first being discussed. Tom became a bit agitated by student responses that were mostly complimentary and only barely critical of each others’ work.

“C’mon. Stop being so nice. You can be harder on her/him!” Thom explained this outburst by saying that West Coast students had trouble being critical of each other’s poems because they were afraid of giving offence, whilst those on the East Coast tended to be much too critical and competitive, fighting their way to the top over the bodies of the poets whose work they sometimes happily tore to pieces. Soon the chorus of “be harder” started to ring through class spontaneously (followed by giggles) after the students had finished describing most of the good aspects of the poem, but had just barely touched what needed improvement.

Thom waited until everyone else except the poet had spoken, before summing up what had been said and usually adding something important that the students had missed. Thom may have walked into the class the first day by projecting his hard guy leather rebel persona, but he was, on the contrary, the most careful reader and capable writing instructor I’ve ever experienced. Thom returned poems with helpful micro-level (correction of spelling, punctuations and word order, and crossing out overwritten phrases leaving just the essential words behind) as well as a paragraph of macro-level comments (the overall effectiveness of the poem and/or where it fit in contemporary American/English poetry). As a result of this, I can remember his writing class as being orderly, respectful, inspiring and productive. In addition, I don’t remember students ever questioning his judgment.

Within a few weeks, everyone in the class, due to the intensity of the class’s discussions and comments, knew who were the better, more interesting and/or controversial poets. Despite this, Thom gave everyone equal time in class. He was one of the few poetry teachers I can remember who carefully kept track of the time each students’ work was discussed. He waited for the end of the maximum half hour of discussion before he made his summation and delivered his final judgment and/or recommendations.

Thom shared his personal life in class only once that I can remember. That day he asked us if we thought he was too old or physically over the hill. We assured him he wasn’t. I mentioned that he didn’t have anything resembling a beer gut which most men his age had and that he had all his hair. This seemed to put Thom back on top and we got on with the class.

After listening to others’ poems being critiqued the first two weeks, I submitted my own poems for consideration, a long one in three parts called “Coming Out,” and two shorter ones called “Subway” and “To Harry in the Hope of Your Speedy Return.” Because Thom was gay, I felt comfortable submitting the “Coming Out” poem to class for critique. The students in general liked it and weren’t repulsed by the gay subject matter as students in other programs were a few years later. Thom’s students, whatever their sexuality, were able to offer helpful recommendations on how to tighten up lines or rearrange word order to make the poem stronger. After class ended and most of the students had left the room, Thom confided to me that many times he’d tried to capture the spirit of a gay march or protest, but hadn’t been able to. My “Coming Out” poem, however, in its third part, was able to capture that raw sentiment with the image for example of ““I tore my bedsheets to make a banner” (which was about the first march on Washington for gay rights in 1979). He also liked the images of the “soldier boy” and “his boots/laughing on my ribs.” The soldier boy image was one he would refer to in his correspondence for years after I had graduated from Berkeley and gone onto graduate school.

I also remember the laughter in Thom’s class and the constructive criticism when L.R. read her two poems “Femme Dykes” and “sitting on a fence” about blowing up traditional stereotypes and not wanting sometimes to identify with a specific sexuality, which I later published in the first issue of No Apologies. It was then I understood another reason I enjoyed writing workshops so much—to hear previously unpublished work read by as yet undiscovered authors—(and later, the thrill being the first to put it into print). This laughter also rounded out the class when someone, I think it was Marina, wrote a cento for the last class, taking one or two memorable lines from the students’ poems and putting them together into a poetic valediction.

I took Thom’s compliments about my poetry as a sign that he would be open to discussing my writing during his office hours which I tried to sign up for each week. That was when I discovered that even though Berkeley had 36,000 students on 12 campuses, you could still see professors once a week for ten or fifteen minutes. All you had to do was sign up in advance for the professor’s mandatory office hours on the bulletin boards next to their doors in the attic of Wheeler Hall (At least that’s where most of my professors had their offices with windows looking out onto the cement urns at the roof’s edge).

And my visits continued even when I was no longer in Thom’s poetry class. In addition to discussing my poetry, I also talked about readings I was attending in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury and Mission districts, both hotbeds of young, experimental writers, my new relationship with Harry Britt, and how I was getting on as a working student. Thom, on his part, however, confided very little to me except that when he’d come to California on a scholarship it had also been difficult for him to get established and to stay.

Some weeks only a few students would show up, so Thom would give me an extra time slot or two of his time. It was those days that I couldn’t believe my luck as Thom discussed even in more detail, the tricks and tools of a poet. During one of these sessions, Thom took out one of the computer punch cards he gave to students to register late for his class and wrote his home telephone number on the back of it. I don’t remember what prompted him to do this, but I only rang this number rarely to talk to Thom about poetry, to tell him about a reading or my gay literary magazine, No Apologies, or to request a recommendation to graduate school.

After I left Berkeley and during the time I attended Brown we continued to correspond at least three times per year. In June 1983, Thom wrote to apologize for not being able to make it to my graduation party. On the back of a Poetry Comic Card #7, showing Walt Whitman sitting in an armchair watching television dated 7 June 1983, Thom sent me his “Congratulations” and wished me “a good summer” but apologized for not being able to attend my “graduation party.” Other times he wrote to confirm he’d received my request for recommendation letters to graduate school. In January 1984, he sent another postcard, this one featuring a short-haired blond man at the Air Force Academy holding its falcon mascot on his arm. Thom commented on the back of this postcard that that man looked “like the “soldier boy” at the end of your poem!…” Thom thanked me for sending him a copy of No Apologies’ first issue and for the recommendation forms for me for graduate school. He was confused though, “Now, one goes to Harvard, one goes to Brown, but where does one other one go?” He guessed that it went to the graduate program at Berkeley and he was correct.

I also phoned or wrote him during this time, asking him to read at No Apologies book parties in November 1983 at the Intersection and in May 1984 at New Space, a converted store front gallery, reading and dance space across the street from New College at 19th and Valencia. Thom, however, declined both times and Steve Abbott and Harold Norse respectively were the featured readers for those two events. Both times Thom thanked me for my invitation, but declined gracefully.

Only once did I see Thom in San Francisco when he wasn’t as eloquent and graceful as he’d been in class or on the phone and which also revealed a bit about his own private life including his recreational drug use. One Friday evening as I was walking on Market Street at 15th near where I lived, I saw Thom stumbling on the pavement. I walked up to him and asked “Thom, are you OK?” Instead of being able to speak to me, however, he could only gurgle and giggle in response. He must have been high and on his way from the N-Judah Duboce Park stop. Thom continued down the Market Street hill in this state.

Whilst at Brown from 1984 to 1986, Thom and I exchanged postcards and letters at least bi-annually, four of which I still have and which are fairly representative of our correspondence from that time. (Taras Otus also contacted me in December 1984 after some of my poems where published in Bay Windows in Boston. We got together at least once in Cambridge to talk about poetry and share our work). In March 1985 I sent Thom a long letter in which I asked him whether I should remain at Brown a second year and get my MA in creative writing. So far, I’d experienced opposition at Brown due to the homoerotic poems, the continued publication of my gay magazine, No Apologies (which ironically had won me the scholarship to Brown) and the response of some of the faculty, their spouses and fellow students to my partner’s presence at some campus readings. Unfortunately in the spring of 1985, even though I had been a fastidious student, attending all my classes and completing my assignments, I was passed over for a teaching assistantship for the next year. This was despite the 15 poems I’d had accepted or published, the three readings I’d given or sponsored on or around campus and the two major readings I was scheduled to give—one at the Small Press Fair at Madison Square Garden in New York City and the other at the Modern Language Association in Chicago.

About this time I had also been told all writing fellowships were being reconsidered. My response to this was to go home and see if I had enough boxes and suitcases to pack everything into to move back to San Francisco. Given the choice of borrowing $8,500 to complete my degree in creative writing or moving back San Francisco to continue with my magazine, the latter not the former seemed more reasonable based on my experience.

Around this time, I sent a letter to Thom in which I wondered whether the move to the East Coast had been worth it. Thom responded in a letter dated April 8 (1985). He said he was “glad that you are shaking them up at Brown…and I’m sure Philip Levine is glad too,” because he felt Levine had also done that at Berkeley even though it was something Thom felt he had “never been able to do” there. Thom also wrote about the value of getting a degree in teaching creative writing. He said that he sort of “fell into it.” He said that he felt teaching writing at a very elementary level—“giving them that starting push,” was “good” and “honest,” but he didn’t feel that writing “needs…or should be taught beyond that level.” He went on further to say that the “Writing Workshop style seems…responsible for the general wimpiness in too much American poetry.” But he concluded that the best thing for me to do “would be to try to get an MA in poetry.”

Then he went on to share that it had also been a “difficult semester” for him also. That even though he: “did a lot writing last year, which made me happy,” he had still decided that his next book would not come out until 1992, à lá Robert Duncan, who published a book only every ten years.

In addition, Thom wrote at the top of the back of the letter’s envelope at the top: “P.S. It gets slippery on that big hill you’re on, esp. in the winter, doesn’t it.” I can’t help thinking he was referring to more than meteorology and geography.

Reverse of envelope of letter from Thom Gunn to Bryan R. Monte, 8 April 1985

After his receipt of issue four of No Apologies which featured the second part of the long memoir by Harold Norse and an in-depth interview with Dennis Cooper, Thom wrote me a thank you note on 22 May 1985 on the back of a postcard featuring the Martin Theater in Talladega, Alabama. It was sent to my address at the Graduate department (where I assume the secretaries and anyone else could read it in my open cubby hole before I collected it). He wrote he liked the Cooper interview and my poem Heterophobia (later published by The James White Review as “The Visit”). He wrote me that “Heterophobia” was “good, interesting, gutsy, original.” About my other poem, “Daddy Dearest,” Thom said it reminded him of a man I’d written about “before, in a poem where he was a soldier boy.” Thom wished me luck at the private boarding school where I was about to teach that summer and warned me not to have “too many illusions about it” because it might turn out to be “a more tight-assed place then where you are.”

The next piece of correspondence I have from Thom is dated 16 July 1985. He sent it to that “tight-assed” school where I assisted with a poetry and a film class and was the instructor for track. I had written Thom about a contract an editor had sent me for an anthology. The contract prohibited me from republishing my poems chosen for the anthology for three years. I didn’t know whether I should agree to this because they’d taken many of my best poems like “Intimations of Frank O’Hara,” “Coming Out,” (the one with the soldier boy) “To Harry in the Hope of Your Speedy Return” (which Thom had said reminded him of Ezra Pound’s letter of the merchant’s wife letter in the Cantos) and “The Visit.”

In response to my question, “Should I sign?” Thom wrote that he found it “odd” that I had to sign a contract for a group of poems and not a book especially if I was only getting “two copies” of the anthology in return. He mentioned his own publishing experience and said that “the only times I have been asked to sign a contract for a poem….have been with The New Yorker which pays a great deal of money.” Thom’s advice was that I should either “a. ask for my poems back and send them elsewhere or b. sign the contract with the intention of breaking it.” Thom went on further to explain that “Obviously a. is the more honest.”

I had also sent Thom copies of the poems the publisher wanted me to sign the contract for including “The Mistress of Castro Street” and “Intimations of Frank O’Hara.” Thom called the latter “a real triumph in its assurance of tone, its certainty and tact, and….unashamed sexuality that reminds me of Marlowe in Hero and Leander.”

Thom ended the letter by saying he’d just attended a reading by Robert Duncan lamenting that Duncan was “the only great poet left alive” due to Basil Bunting’s and Cunningham’s deaths. “And, given his kidneys, I’m not sure he’s left to us much longer.”

The next month, I received Thom’s recommendation (on University of California, Berkeley stationery) dated July 30, 1985 for a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts to help fund my magazine. First, Thom praised my magazine saying it was “innovative, bold and interesting” and that it was “one of the few magazines whose main concern is with Gay literature rather than…Fall fashions, cultural chit-chat, etc… and that its approach is consistently serious and responsible.” Then he mentioned my ability as an editor saying in the last five year he had “watched with interest the growth of his editorial talents in connection…with his poetic talents.” Thom called me a “dedicated and discriminating editor” and my magazine “worthy of whatever support” the NEA “could give it.”

I was over the moon with such a recommendation (and also one from Felice Picano, the editor of the Seahorse Press). One afternoon, out of the blue, I was telephoned by a woman from the NEA, who asked if I could raise half of the magazine’s budget from private investors. Instead of lying and telling her what I now realize she wanted to hear, I told her the truth—that I didn’t think I could raise 50% of my operating costs for the magazine’s expansion from private investors. (I could barely scrape enough money together each month to pay my rent and groceries!) This honest answer, unfortunately, probably doomed my request. I don’t know how far it got and if that was the last hurdle, but at the time it didn’t matter. I was exhausted from working two and sometimes three part-time jobs to pay for graduate school and keep a roof over my head let alone go out fundraising for private backers for a literary magazine.

The last piece of correspondence I received at Brown or have preserved is a short note on a piece of cardstock paper in an envelope dated 15 November 1985. This was in response for a letter of recommendation to a graduate school that was to be sent directly to the university without me seeing it. Thom, forever the anti-establishment hippie, wrote: “Now you can see it and still have waived your right to see it!”

I returned to San Francisco in February and July of 1987, the first time during a winter school holiday and the second after finishing my first and last year teaching high school in Massachusetts. While in San Francisco that February, I stayed at Edward Mycue and Richard Steger’s apartment and also visited James Broughton and Steve Abbott. On 16 February 1987, on the way back from Steve’s, I stopped at Thom’s. This is my journal entry:

On the way back, I stopped by Thom Gunn’s house….Thom was on the phone, so one of his roommates let me in. When he came in the room, he was as shy as always, wearing a leather band with flat metal studs on his left wrist. He’s thinner than the last time I saw him….His back was bent forward and he hugged himself. We talked a little bit about Massachusetts versus California—weather is warm, it’s spring already, drivers are nicer, etc. and I told him his picture was in the English Lit. textbook we use for the upper levels. He asked which one it was, but when I mentioned the title, he didn’t recognize it. I said it was the one in which he had a beard and was wearing a black, Zig-Zag T-shirt. He still didn’t remember it. A few minutes later, he walked up to me and shook my hand after we made a date to get together Friday at 5 at the Twin Peaks Tavern.

We met that Friday in the Twin Peaks Tavern at the busy corner of Castro, Market, and 17th Streets. As the rush hour traffic whizzed by and the music played not as loudly as other places in the Castro in the bar, Thom and I talked about my first job teaching creative writing in Massachusetts’ high school. I told him I intended to return that summer to San Francisco, that I’d spent the last week contacting San Francisco employers via the Brown University graduate network. A hotel and an advertising firm had both promised me work, so we both drank to my imminent return in just a few months for an hour or so before we both went off to our next appointments expecting my return that summer.

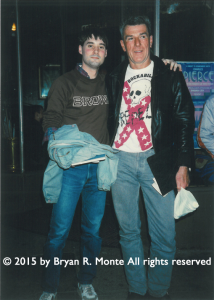

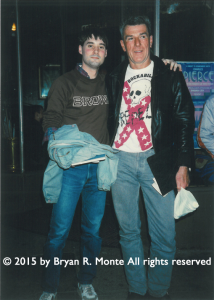

In July 1987, Thom’s was one of the first places I stopped to show off my new car and tell him about my road trip across the country. (My journey started just 30 miles west of where the Pilgrims landed with a detour north at Iowa to Minnesota to see Phil Willkie and Greg Baysans at The James White Review. (I attended a writing camp in the Wisconsin woods sponsored by JWR and led by poet, Robert Peters). Thom was happy to see me and posed for a photograph with me.

Bryan R. Monte & Thom Gunn in San Francisco, July 1987

The next record I have of Thom is a black and white photo postcard of a short-haired, young, bare chested man with a chain around his neck looking at his shadow against a white wall. It’s dated Nov 16/88 more than a year later and it was sent to my address in Silicon Valley with the instructions to “Please Forward” if necessary. I had invited Thom to a reading of my long poem, “Neurotika.” It featured snippets of my own erotic misfortunes and the escalating AIDS crisis in San Francisco interlaced with music loop of Bryan Eno’s Music for Airports, part 2, gay travel magazines reports about where homosexuality was criminalized in the world and newspaper reports of the spread of the world-wide AIDS pandemic. Thom’s response to my invitation was short saying he wouldn’t be able to make it because he would be in Portland then. He did however wish me “Good luck.”

I saw Thom for the last time at a reading he gave at Black Oak Books in Berkeley in 1992. It was just after the publication of his fourth major poetry book: The Man With Night Sweats. I attended that reading with the late poet and doctor, Ronald Linder. It was a cold, overcast, foggy day and I remember all the lighting was switched on inside that enormous store.

Thom still recognized me without me having to introduce myself even though it had been more than a decade since I’d sat in his class. He smiled, chatted with me briefly and signed a copy of Night Sweats and also a broadside of the book’s title poem, “a gift from Black Oak Books”…“on the occasion of the reading by the author.” As he’d mentioned in his letter to me in ’85, Tom had kept his promise not to publish again until 1992.

I corresponded with Thom at least once more that I remember after I moved to Europe in 1993. In 1994 I sent him my poems arranged in a book-sized collection entitled Neurotika asking for his opinion and, if possible, a book blurb. Thom posted the poems back to me a few months later with a letter that I have either temporarily misplaced or lost during one of my four moves during the next seven years. I can’t remember exactly what was in the letter, but essentially it said that the publishing world had changed considerably since his first book, and that he no longer knew where to refer me. I did notice, however, that Thom had taken the time to go through my entire manuscript, just as if I were still in his workshop, and edit it. For that I was grateful, even if it seemed I was on my own to find a publisher and/or an agent.

More than twenty years later, I still consider it a privilege to have studied and corresponded with Thom Gunn. He was a great poet and a modest and masterful teacher. He gave me the start that I needed and offered advice for years after I’d left university. This kept me going through the dark years when I had no time to write whilst trying to keep my head above water financially and trying to forge ahead with my teaching career in a new country. Now that due to my disability I have time to write again, I look back on Thom, his class, and my classmates fondly. As I sit in a bookshop in Amsterdam listening to the Westerkerk’s two o’clock chimes signalling it’s time for Amsterdam Quarterly’s monthly writers workshop to begin, I realize that Thom taught me all I ever needed to know about writing and teaching writing—and I want to do the same for these writers.