Bryan R. Monte

Write/Right to Speak

My gay graduate years at Brown University, 1984-86

© 2024 by Bryan R. Monte. All rights reserved.

In June 2024, I received an article in my LinkedIn feed from Brown University entitled: ‘So That We May Write and Be Heard’ about a Stonewall House exhibition concerning the university’s Lesbian and Gay Student Association (LGSA) from 1983 to 1998. Coincidentally, I had also been working on my memoir of my Brown graduate writing fellowship from 1984 to 1986 since the previous autumn. I remembered many things in the documents that Ellen Huggins, Anna Marti, and Anthony Boss uncovered in the ‘tons and tons of boxes’ which no one had examined for decades. Due to this, I feel it is appropriate to share some of my journal entries and memories about my experiences as a gay man at Brown about some of the important LGSA or LGBTQ-related events on campus during that time.

As I wrote in a previous memoir entitled: ‘The End of the Beginning’, https://www.amsterdamquarterly.org/aq_issues/aq27-beginnings-endings/bryan-r-monte-the-end-of-the-beginning/: ‘On 28 March I received an acceptance letter with a fellowship to Brown University’s Graduate Writing Program.’ I was overwhelmed by the honour and felt the only choice I had was to go.

However, there were many unforeseen consequences to accepting a fellowship to a university I’d never visited, in a part of the country I’d never lived. I didn’t anticipate the degree of culture shock I would experience. In San Francisco, I lived in a working-class, LGBTQ-friendly, multi-cultural, rent-controlled, Mission District neighbourhood, with cheap restaurants and cafes, frequent poetry readings, and several leftist bookstores. Here I had founded No Apologies: a magazine of gay writing. In contrast, when I arrived on Providence’s College Hill in July 1984, I found an upper-middle-class, much less LGBTQ-friendly and multi-cultural neighbourhood, with few, inexpensive restaurants, cafes, and flats.

And I remembered too late Thom Gunn’s comment about the difference between East Coast and West Coast writers’ workshops as detailed in my memoir, ‘The Long Workshop: A memoir of Thom Gunn, 1982-1994’ at https://www.amsterdamquarterly.org/aq_issues/aq12-writers-writerswriting/bryan-r-monte-long-workshop-memoir-thom-gunn/ to anticipate the type of reception my work might receive. ‘… East Coast (students) tended to be much too critical and competitive, fighting their way to the top over the bodies of the poets whose work they sometimes happily tore to pieces.’ versus ‘… West Coast students had trouble being critical of each other’s poems because they were afraid of giving offence.’

At Brown, I soon discovered that when one’s poem came up for consideration, it was as if the instructor had shouted ‘Pull’ and the students raised their rifles to blast another clay pigeon contender out of the sky. And as far as discussion of my gay-themed poems were concerned, students openly protested with: ‘This poem shows me a world I don’t want to see’ to which I would respond: ‘Congratulations, sir/madam. Welcome to the world of ART!’

Unfortunately, the welcome I received from some of my writing instructors was also less than positive. One instructor, who had assigned Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own as required reading, labelled my poems about the AIDS epidemic as ‘hysterical—What if it doesn’t turn out to be that bad?’ Another objected to my frequent depiction of homophobia because: ‘You can always hide’. ‘Where?’, I thought. ‘There’s no African-American or Hillel-like Rainbow House on campus for lesbians and gays.’ (There wouldn’t be for another 39 years). Instead, I said: ‘When has passing ever been the way to liberation?’

A few weeks later I attended my first LGSA meeting in Faunce Arch. In a journal entry from 19 September, I described my first encounter with this group and the state of its meeting place:

The room and furniture looked…battered. I suggested to young man there…that all the broken furniture…be moved to the edge of the room and covered with something and people at the meeting only use the sturdy chairs or sit on the floor because some people’s lives were ‘already broken enough’. I told a student I was interested in helping with projects. He suggested the [organization’s] newsletter. I said I wanted to set up for dances or organize field trips. [In addition, I met] another student who recognized me because he [had] spent time with Steve Chivers, one of No Apologies #3’s writers in Provincetown.

Nonetheless, despite the less than warm reception from the GWP students and instructors, and the state of the LGSA office, I hit the ground running. Previously, I had contacted Ray Rickman at Cornerstone Bookstore in Providence and in October I held a well-attended gay poetry reading there. However, few GWP students attended. One was Claudia (née Robitaille) Grace (1954-2014), a fellow poet, with whom I became fast friends. Another was James Dalglish, a playwright. Soon, No Apologies was on sale at the Brown University, College Hill, Cornerstone, and Dorr Wall bookstores.

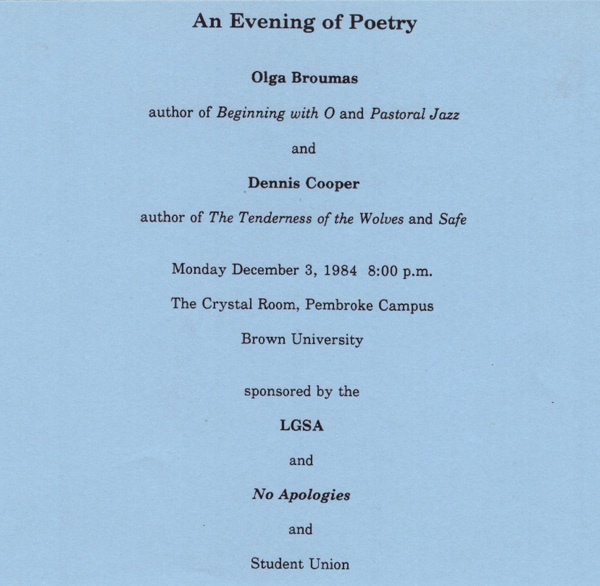

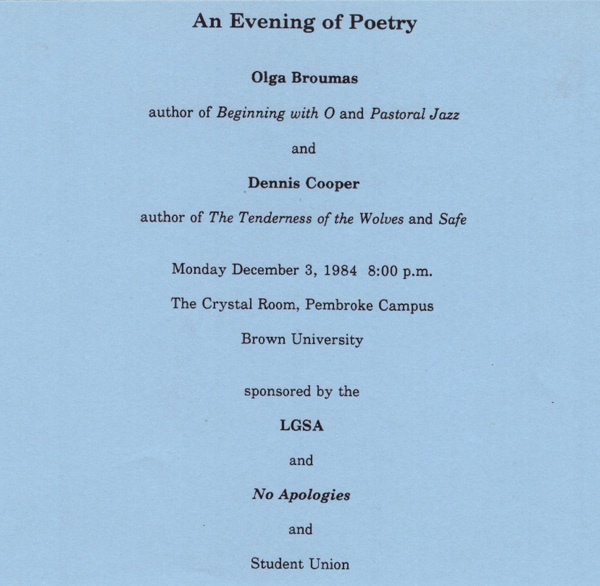

Grace was the only GWP poetry workshop student who consistently supported my work during discussions and who contributed work to No Apologies, even though she wasn’t a lesbian, but rather what one would now call an ally. In addition, Grace organized a surprise birthday party for me at her Eastside flat in early November and helped persuade Olga Broumas to take part in a reading I wanted to hold on campus in December with Broumas and Dennis Cooper.

Two students I met rather quickly at LGSA meetings were known as the two Steves. The first was Steve S., a tall student with a square jaw line and short, dark hair. The second was Steve Gendin (1966-2000), who was also tall, but somewhat quieter and had longer, fuller dark hair, an angular face, and deep, dark eyes. Gendin appears in my journal for the first time on 2 December 1984 in reference to a financial problem. I wrote that I had phoned him and discovered that he ‘still doesn’t have the money for the (LGSA) reading as of tonight!’. I was shocked and worried that if the LGSA or I were unable to pay Broumas’s and Cooper’s speaking fees, the good reputation I’d been building, on campus and in Providence and as No Apologies’ editor, might be quickly undone.

However, to my relief the next evening, both Gendin and I arrived at Pembroke’s Crystal Room chequebooks in hand to cover the fees. It was the first of many incidents where the LGSA literally had my back.

Bryan R. Monte, Broumas/Cooper Reading Announcement, half-page flyer, 1984

Later that month, on 8 December, I met Ben Hu and Christopher Jarvinen at an LGSA dance.

During my first, difficult months on campus, the Brown LGSA was a great source of emotional, social, and creative support. It was an enthusiastic group of students who openly discussed issues facing sexual minorities on campus and in the world. It provided a safe environment in which to socialize in contrast to the gay bars in high crime areas downtown, where Wesley Gibson (also a GWP student) and his partner, Tom Wingfield, unfortunately witnessed a stabbing at close range.

Furthermore, I found the LGSA to be a very good forum for airing matters of the heart in a supportive environment, especially breakups, which seemed to happen mostly around the end of the semesters or over university holidays. In a Pembroke canteen after the meetings, we could lick our wounds and discuss our heartbreaks as well as other problems we were experiencing.

One of the hot discussion topics during my time at Brown, which was mentioned in the Brown LGSA LinkedIn article, was speculation about who had ripped out some pages from the LGSA’s commonplace book. Its bookplate had this quote from William Lloyd Garrison: ‘I AM IN EARNEST—I WILL NOT EQUIVOCATE—I WILL NOT EXCUSE—I WILL NOT RETREAT A SINGLE INCH AND I WILL BE HEARD! and below it, the admonition: ‘THIS BOOK IS FOR THE LGSA THAT WE MAY WRITE AND BE HEARD. SO WRITE…’ Over the years, LGSA students continued to add their thoughts, observations, and opinions while speculating on what the missing pages might have held.

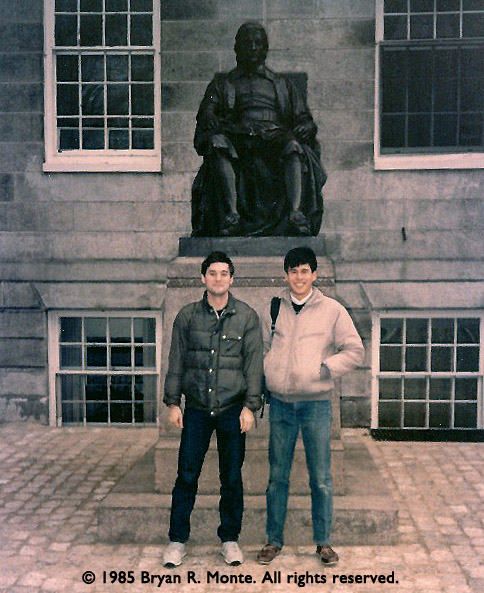

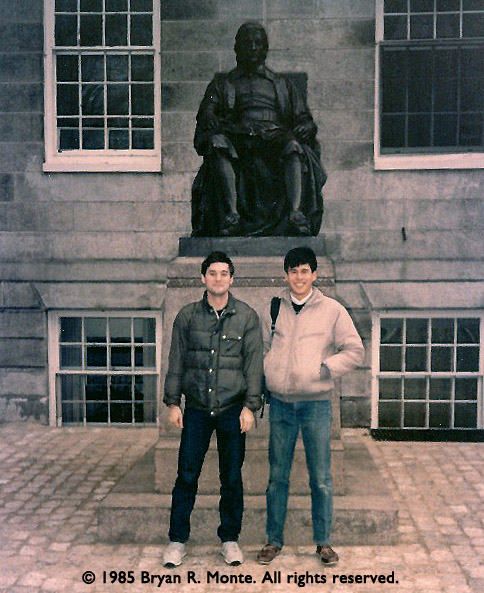

In the company of some of these LGSA men and women and their allies, I travelled to places I wouldn’t have seen or enjoyed as much without them. With Hu I visited Harvard, where we had our photo taken in front of the founder’s statue. With Jarvinen I visited Provincetown in February. We walked through the nearly empty town and the deserted, wind-swept dunes. With Grace I went to Bristol Community College with John Landry to hear San Francisco poet Neeli Cherkovski read. With Dalglish and Hu, I saw Mephisto on campus and with Dalglish and other GWP students I saw Amadeus at a Massachusetts movie theatre.

Unknown photographer, Bryan R. Monte and Ben Hu, Harvard Yard, photograph, 1985

Dalglish and I ran into and hung out with each other a lot. He was also present when I had a brush with one of Brown’s student royalty. We were standing in line for ice cream when I felt a woman behind me stick her hand in my back pocket. After we got our ice cream, I took him aside and said: ‘I think that woman was trying to steal my wallet.’ Dalglish looked at her and then me and said: ‘You idiot! That’s Cosima van Bülow. She doesn’t need your money!’ (Amy Carter and Prince Faisal bin al-Hussein of Jordan were also on campus during this time).

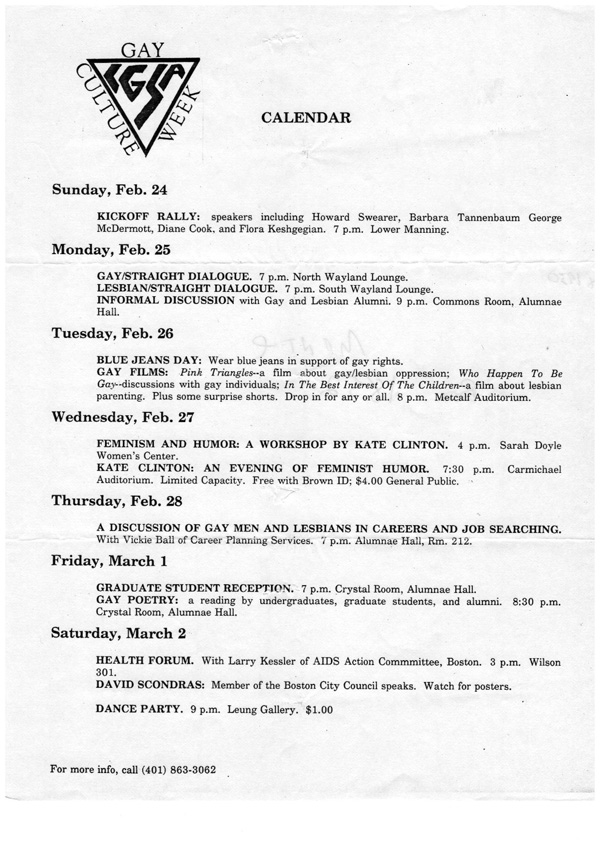

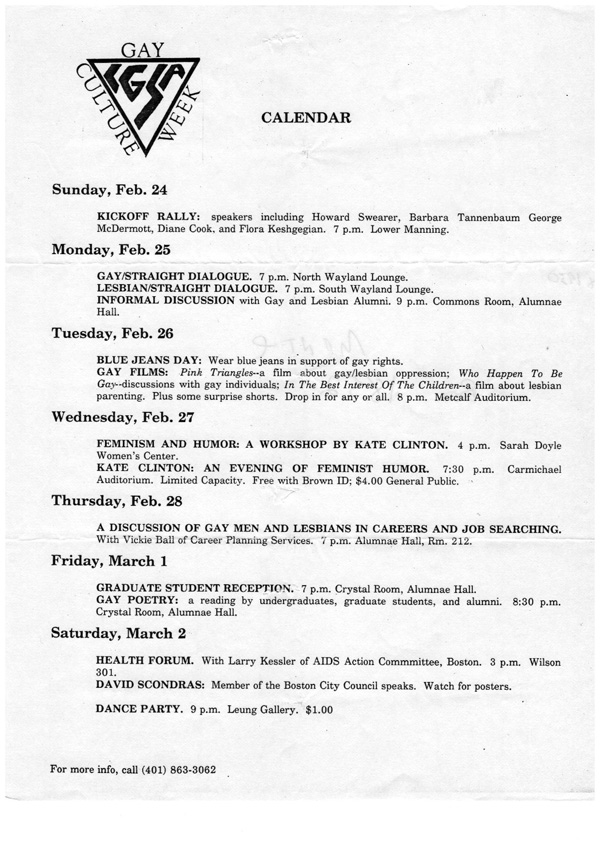

In addition to socializing, I also organized two events for the 1985 LGSA Culture Week: a film night and a reading. However, Pink Week, as we referred to it, was not without conflict on campus. On 3 March 1985, I wrote in my journal about the Tuesday film night event:

…[the film] Pink Triangles, came in and the Brown Film Society donated their [a projectionist’s] time, and a projector to show the film in Metcalf. Over 150 people attended the screening which I introduced along with encouraging the audience to join the candlelight vigil on the Green at midnight. (The 6 x 5 ft. pink triangle announcing the week’s events in front of Faunce House had been vandalized the night before).

(During the vigil),…a group of 10-12 people, wearing hooded sweatshirts, ran up…(They were) definitely up to no good since the [main] gate was closed and there was no place those guys could have been going that late at night other than to confront us. They scared the shit out of 3 security officers, who had been acting like shits (to us) until these guys (appeared). One of the deans was also there… I asked him: ‘What the hell was that?’ after they [were] gone. (Our people were very good. They didn’t say anything to taunt them)…The next day, and for the rest of the week, there were no less than 2 security cars parked outside of Faunce Arch.

The Friday poetry reading was sponsored by the LGSA and the Undergraduate, Graduate, and Alumni Student Associations. It included six readers and was held in Pembroke’s Crystal Room. Nearly 50 people attended and it was a wonderful, arty event.

LGSA Gay Culture Week Calendar, 24 February to 1 March 1985, flyer

However, despite these happy events, anti-LGBTQ surveillance and opposition seemed to grow during US President Ronald Reagan’s two terms. In autumn 1984, a tape of my poem, ‘Coming Out’, was stolen three times from its videographer after three separate recording sessions—the first time out of her backpack while at Hillel House at lunch, the second time from her car, and the third time from her flat. She finally told me she wouldn’t try to record my poem anymore saying: ‘It’s obvious someone doesn’t want anyone to see this tape.’

In addition, my correspondence with gay bookstores in Canada and the United Kingdom was opened and stamped by customs, and I received late-night obscene phone calls every time a new issue of No Apologies hit the bookstores. Furthermore, during this time, Brown students protested the CIA’s recruiting on campus and President Howard Swearer chose not to extend the university’s non-discrimination clause to gay and lesbians after the recommendation of Brown’s student government. Swearer was later quoted in a Brown Daily Herald article from 19 October 1987 headlined ‘Many Students “Indifferent”; Some Sorry, Some “Happy”’, stating the reason he hadn’t extended this protection was due to ‘a concern over the precedent of singling out yet another category of persons for special attention.’

It was good that Pink Week went so well because just over a month later, on 4 April 1985, I discovered I had unfortunately:

‘No summer [teaching] job,…no encouragement from Levine to do a book, and no teaching assistantship for next year at Brown. All I need now is for [Allen] Ginsberg to tell me to ‘fuck off’ tomorrow when I give him a copy of No Apologies, and the disaster will be complete.

I was very upset that I hadn’t receive a Brown teaching assistantship because I’d had more publications and readings my first year than many of the junior faculty. In addition, I attended my writing classes regularly, read the required texts, and provided marginal and intertextual feedback for my fellow students’ poems. Fortunately, Ginsberg’s reading and his acceptance of a copy of No Apologies #3 quickly dispersed my dark thoughts.

He was wonderful…a grand, enlightened man who oozed love—our radical father telling us all how to be bad and have fun while we’re alive. He sat on the dais and played a harmonium, stomping his feet to the beat while a friend accompanied him on the guitar. A little in the spirit of a revival. In fact, the most spiritual reading I’ve ever attended. Men put their arms around each other or held each other’s hands as Jim G. and I did. [Ginsberg read] ‘Pull My Daisy’, ‘The Green Automobile’, …the entire…‘Howl’ and ‘Kaddish’… [and] also…a few of Wim. Blake’s poems, which he set to music. The best was ‘Tyger, Tyger, which he read with a heartbeat rhythm.

At the intermission, I [broke] through the autograph hounds to give Ginsberg a copy of No Apologies #3…I said: ‘Allen, I’d like to give you something you don’t have to sign, this is for you!’ Ginsberg looked down at the cover and exclaimed when he saw Robin Blaser’s name…’

I published No Apologies #4 later that month. It featured an interview with Cooper, poetry by Broumas, a WWII New York City memoir by Donald Vining, artwork by Wingfield, fiction by Gibson, poetry by Grace, and my essay on the unspoken homosexual discourse or gay gaze in Berlin Alexanderplatz, among other pieces.

I sent 40 copies of No Apologies #4 to A Different Light Bookstore in New York per their standing order, (it would increase to 50 for issue #5), and five or more copies to gay or gay-friendly bookstores in Berkeley, Boston, Denver, Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York City, Providence, Provincetown, San Francisco, London, Montreal, and Amsterdam, and to the university libraries at Brown, SUNY Albany, and Wisconsin. I felt that if I had accomplished nothing else my first year at Brown, then the publication of No Apologies #4 would make up for it.

In addition, I took three elective courses at Brown that inspired me to write. The first was Professor Michael Silverman’s semiotics course on Berlin Alexanderplatz, which included watching one or two episodes of the Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s television series per week as we read Alfred Döblin’s novel of the same name. Fortunately, it was in this course that I met artist Dawn Clements (1958-2018). Clements and I also took another course with Professor Silverman on Michel Foucault in the spring of 1986. My details about Clements and I and these classes are in my memoir entitled ‘Paper’ at https://www.amsterdamquarterly.org/aq_issues/aq24-media/bryan-r-monte-paper-in-memory-of-dawn-clements-1958-2018/.

My second elective was a comparative education class taught by a professor, whose name I have forgotten. This course proved to be a delight because its reading material consisted mainly of 1950s and ’60s novels about teaching and young people such as Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim (great for its depiction of the crazy world of university teaching assistantships and politics), Evan Hunter’s Blackboard Jungle, and Bel Kaufman’s Up the Down Staircase.

Another reason I enjoyed this course was my guilty pleasure of observing many of Brown’s baseball team players, who were enrolled in this class and who wore their team shirts and brought the rest of their uniforms and equipment—gloves, balls, bats, cleated shoes, and uniform trousers—in large, dusty, sports bags for practice after class. Splayed across the standard-size student desks that didn’t quite fit these much larger athletes, it was hard to miss them. Perhaps they, as I, were hedging their bets in case they didn’t make it to the majors (or the minors for that matter).

In autumn 1985, I took another required GWP poetry workshop and an elective semiotics course. Unfortunately, both courses required a total of 14 papers, so I had little time left for creative writing that semester. Despite this, by some miracle I managed to publish No Apologies #5 that autumn. Its most important pieces were an interview I’d conducted with Felice Picano, a short story by Stan Leventhal, and poetry by David Trinidad. I also went to New York City to participate in a small press publishers’ conference at Madison Square Garden. I shared a half table with gay diarist and memoirist Donald Vining and his Pepys Press. While sitting at the table, I met Marilyn Hacker, a No Apologies #2 contributor, and Samuel R. Delany, her former partner. Both were glad to meet me and enthusiastic about the magazine. I also read my poetry in a hall not far from the exhibit area.

In December 1985, I attended the Modern Language Association’s annual conference in Chicago. I gave my paper on Fassbinder’s unspoken homosexual discourse in Berlin Alexanderplatz. Unfortunately, none of my Brown professors attended my session. While at the MLA, I interviewed for college teaching positions. One Indiana college recruiter dismissed my application saying ‘We’re located in a family town,’ in an attempt to rationalize his homophobia. I replied ‘That’s all right. I know all about families. I grew up in one!’ Unfortunately, my humour didn’t change his mind.

Fortunately, in late April/early May 1986, I had my first major publication. My essay, ‘Living with a Lover or How to Stay Together Without Killing Each Other’, was included in the ground-breaking, Dolphin Doubleday anthology Gay Life, edited by Eric Rofes. Gay Life was also displayed in the Brown University Bookstore. And despite all my trials, in May 1986, I graduated in the past-president-portrait-lined-wood-panelled auditorium of Sayles Hall to Edward Elgar’s ‘Pomp and Circumstance’.

After graduation, I lost contact with most of my student friends including Grace, Clements, and Gendin. Grace founded A.C.C.E.S.S. Art Corp. International, taught memoir writing workshops, and was a UMass Dartmouth creative writing instructor. Unfortunately, she passed away from breast cancer in 2014. I corresponded with Clements for months after graduation and visited her in September 1986 at SUNY Albany, where she was in a master’s program in art. We exchanged Christmas cards and letters, but after that we lost contact for almost three decades. I reconnected with her after I saw her artwork in a London gallery in 2013. We kept in touch regularly via email and Skype and I visited her twice in New York. I saw her for the last time in October 2018 just before she passed away from breast cancer. Over the years, I occasionally saw Gendin in photos of ACT UP street die ins or chained to an office desk or filing cabinet in photos in The New York Times, Time, or Newsweek to protest the government’s and the pharmaceutical industry’s slow response to the AIDS pandemic. In 1991, Gendin and Sean O’Brien Strub founded the Community Prescription Service and in 1994, POZ, a magazine for people with HIV, which is still in publication: https://www.poz.com/. Gendin died of a heart attack while receiving chemotherapy for AIDS-related lymphoma in New York City in 2000.

I also thought about staying on the East Coast and living in or near Manhattan to pursue my interests in writing and publishing. However, when I heard the sirens, car horns, and rubbish truck pickups in the background of Cooper’s and Picano’s interview tapes, saw the dirt that washed off my face every night while in Manhattan, remembered the financial problems of living in NYC—high rent and poor upkeep of rented flats (every bathroom ceiling where I stayed was falling in whether it was in Alphabet City, the Village, or the Upper East Side), and discovered the low or no first- or second-year publishing internship wages, I knew New York was not on the cards for me. Furthermore, I resolved never again to move, study, or work anywhere new without first visiting the city, university, and/or company.

I returned to San Francisco a few years later. From 1989-1990, I reported the weekly LGBTQ news for KPFA-FM in Berkeley. I hoped that one day I would be able to announce a cure, a vaccine, or at least a proven, effective treatment for AIDS. However, this never occurred during my tenure and, due to this volunteer work, which required one hour of prep for every minute of airtime and my educational debt and professional commitments, I was unable to continue with No Apologies. AQ